Scheme a little scheme

Wes Anderson's latest is another masterpiece that many people will hate for reasons known only to themselves and their god.

At this point – some 13 films, eight Academy Award nominations and one Academy Award win into his career – it can be assumed that the average moviegoer aware of him will know will relative certainty what a new Wes Anderson film will be, regardless of its plot, setting, or ridiculously deep ensemble cast. He knows precisely the type of meticulous and fussy* movie that he wishes to make, and he makes the absolute Dickens out of it.

*complimentary

Anderson, since pretty much after the advent of The Royal Tenenbaums, has become a deeply polarizing filmmaker. The jabs at his mannered and pristine style of production design, prose and performance are, at this point, more cliche than those he himself is accused of. He has become the poster child for the word "twee" as epithet, when he really is the natural extension of the optimistic cynicism and nihilism produced from his (and my) generation, weaned on Roald Dahl novels and adventure writing and endless fables of displaced children searching for an adult who understands them. (Or, in the case of some of his films like The Darjeeling Limited or The Grand Budapest Hotel, the displaced adults who feel unstuck in time and in society and grasp about for a home and some semblance of acceptance or self-worth.)

In the case of Roald Dahl, it is all too appropriate that Anderson's previous project was The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More, an anthology film that began life as four Netflix shorts based on Dahl short stories, the titular first of which was the work that finally netted Anderson his first Oscar. There is perhaps no filmmaker ever more suited to the aesthetic and tone of Dahl than Anderson, and the four shorts – staged mostly as direct readings with ingenious set design and played to the hilt by the star-studded cast – are even more faithful and even more of a re-creation of a reader's imagination than his previous Dahl adaptation, the sublime The Fantastic Mr. Fox.

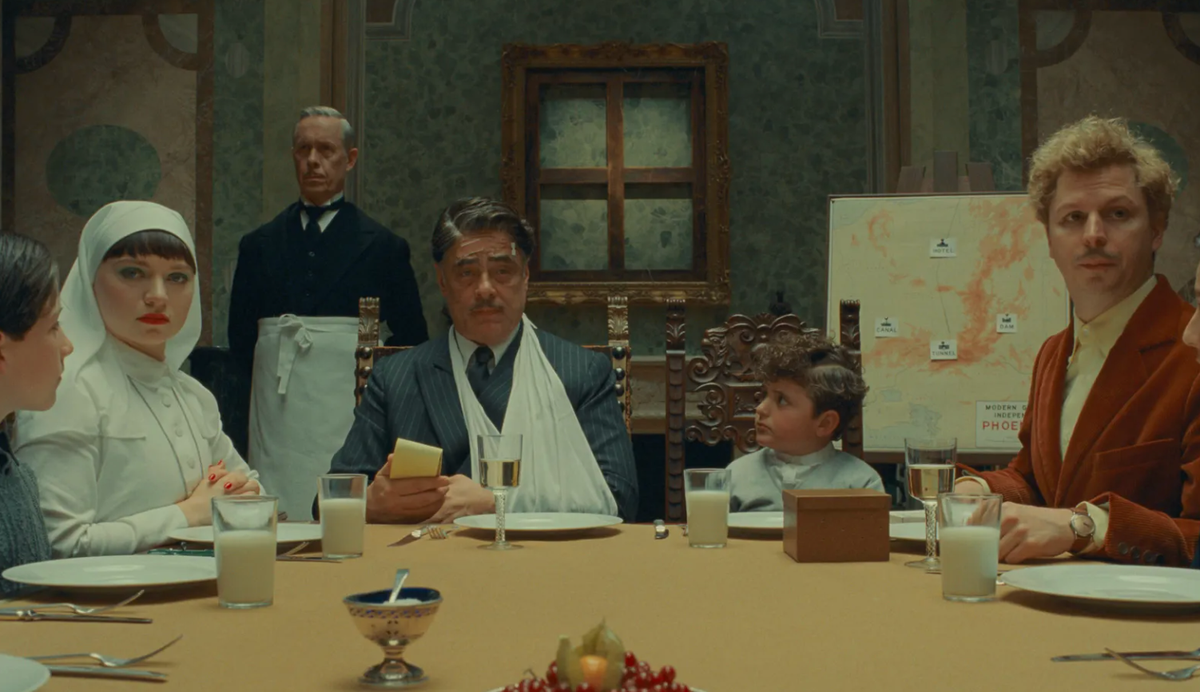

And so it goes with The Phoenician Scheme, a knotty tale of a cutthroat businessman besieged with assassination attempts who must enlist his heir in pursuit of the trans-continental industrial deal that he has envisioned as his life's work. This is the movie where it finally struck me that Anderson is essentially a parallel of Yorgos Lanthimos, the Greek filmmaker who is often invoked as a paragon among those who deride Anderson's too-optimistic (or perhaps just "too cutesy") outlook. Both filmmakers favor dispassionate performance and line reading, both favor a more symmetrical and mathematical style of composition, and both revel in period costumes and elegiac settings. Even their resolutions aren't all that far removed from one another: where most of Lanthimos's resolutions end in some semblance of, "And at the end of the day, we are all destined to face the horrors alone," Anderson's movies usually read much the same, but with an upward lilt: "And at the end of the day, we may face the horrors alone, but maybe we've learned to be okay with ourselves." ... But then again, maybe his characters haven't.

Anderson's output is largely concerned with fathers and sons, but The Phoenician Scheme was written around the time that Anderson's first child – his daughter – was six years old, and has become his first film about a father-daughter relationship.