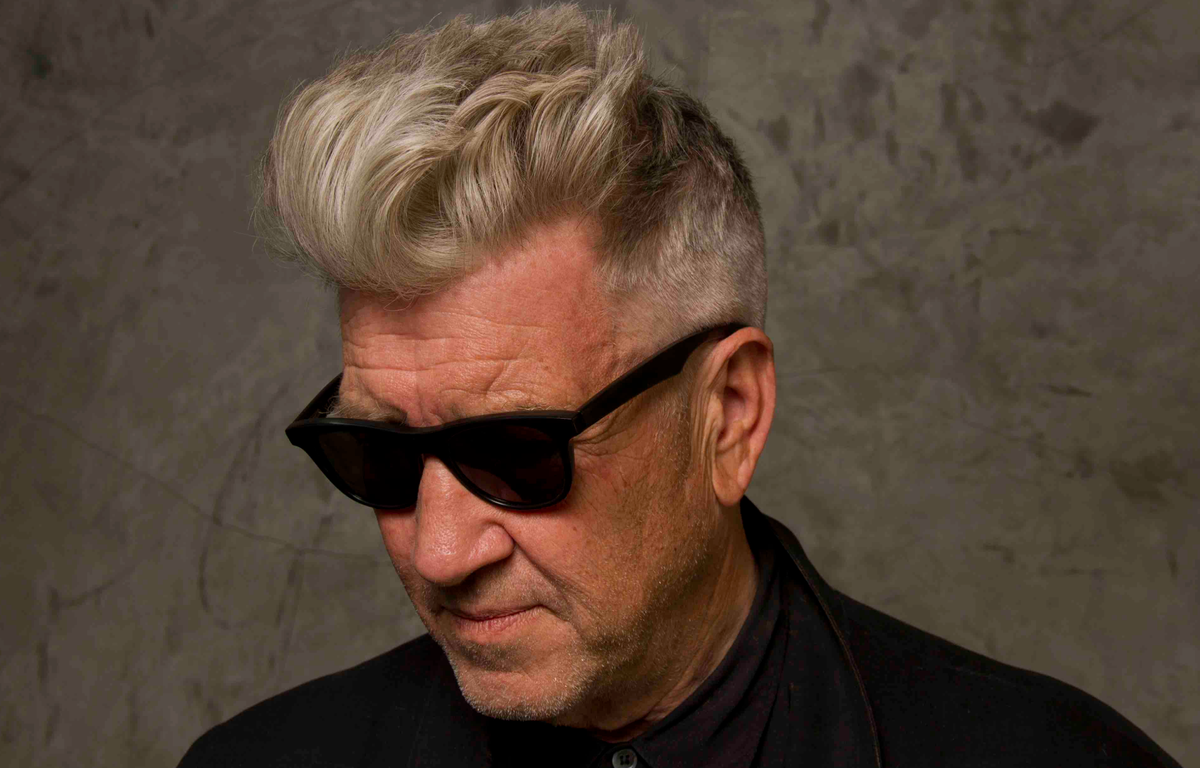

Lynchian

An auteur unlike any other.

For my entire life, the name “David Lynch” has been the universal shorthand for “weirdo arthouse cinema.” David Lynch was many things to many people, but to the majority of America (and perhaps the world) for the majority of his career, he’s been the Eraserhead guy. The guy who makes weird movies about weird people, and if the movies aren’t filled with baffling and nonsensical surrealism that’s inscrutable to most people, they’re full of violence and ugliness and suffering.

Of course, all of that is reductive. There’s basically no way to talk about David Lynch that isn’t reductive on some level, because there’s no way to fully encompass who he was, what he created, and how important his work was to pop culture, but specifically to the filmmaking world.

Yes, he was the avant surrealist horror auteur behind the waking nightmare of Eraserhead, which instantly turned the independent film world on its ear and was so well-known for being weird that there were even jokes referencing it in Archie comics. But his second film was the unparalleled mainstream box office and critical success The Elephant Man, which netted him Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. Yes, he created Blue Velvet, an unflinchingly brutal movie that sickened Roger Ebert to his core, but he also created The Straight Story, a G-rated and thoroughly wholesome movie made for Disney. He turned down George Lucas’ offer to direct Return of the Jedi and instead made Dune, his first and last big-budget attempt at a studio blockbuster, and the experience was so upsetting to him that he never took that plunge again … but then he co-created Twin Peaks, a prime time network soap opera that became a legitimate pop culture phenomenon.

The bulk of his output did indeed focus on the surreal, the otherworldly, the macabre and the ugly, but the man himself was bursting with life, love, and appreciation for everything around him, reveling in melodrama and nostalgia and tear-jerking media that had long been deemed “corny.”

He was a longtime practitioner and advocate for transcendental meditation, the tenets of which wormed their way into many of his works, but perhaps most overtly in the philosophies spouted by Agent Dale Cooper on Twin Peaks.

I recently watched the entirety of Lynch’s filmography as I listened to one of my favorite podcasts, Blank Check, which was discussing his films chronologically. (I had actually just begun rewatching the final episode of Twin Peaks: The Return — one of the final things he created — when the news broke that Lynch had passed away after battling emphysema.) There’s nothing he ever made that didn’t have his fingerprints on it. His works were called “Lynchian” for a reason, because no one would ever mistake one of his films or shows as someone else’s creation. When non-Lynch pieces of art were described as “Lynchian,” it was a disservice to both parties; no one could ever make the things he made, and evoking his name meant there would be no measuring up. That’s just stacking the deck against someone with an unfair comparison.

His films are the very definition of “not for everyone,” and many parts of his oeuvre likely feel impenetrable, offensive, or disconcerting to most people. But during this last rewatch, I came to understand that even though his movies weren’t for everyone, there is an undeniable universality to the way David Lynch viewed the world.

Paid subscribers get to read the rest of this post. It’s that something?