A conversation and a story

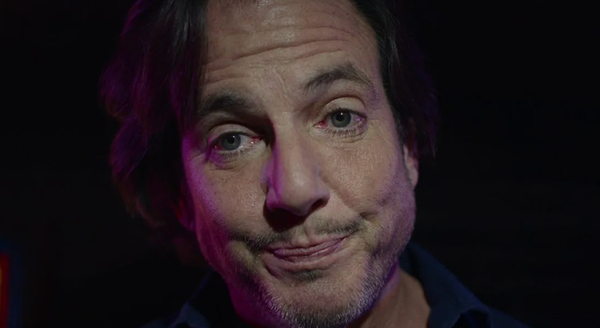

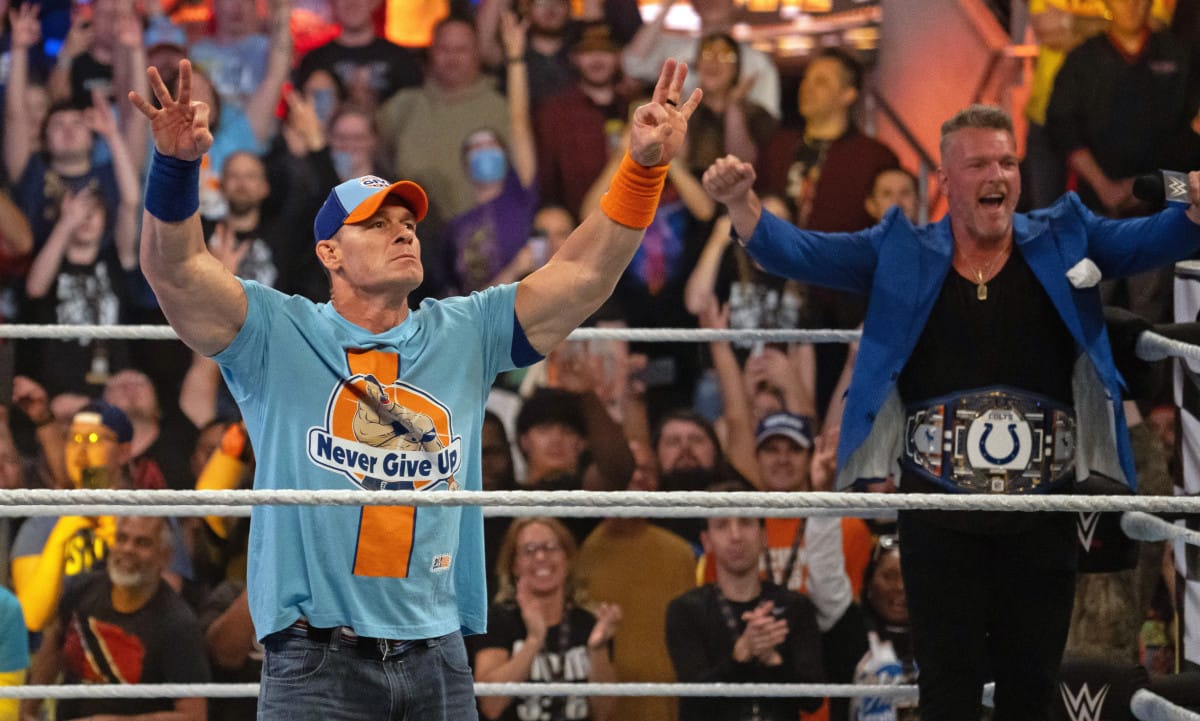

The first item of business in today's newsletter is a podcast appearance I made! It's been a while, but us dyed in the wool podcasters can get right back into the groove like falling off a bike.

I talked to San Diego sports podcast Section 1904 about a ton of stuff, including the dismantling of societal elites, the existence of both sports and pro wrestling in a post-truth America and what that means, and of course we talked a lot of Taylor Swift, because that's my whole shit right now to be honest. You can listen to my appearance at the link above or the link below! Democracy in action!

The second thing I wanted to drop in here today is a first for me, but unless everyone loudly hates it, I'm going to make it a regular thing going forward: an excerpt of a larger story that I'm currently writing.

This is the first part of the first chapter of a novel that is called PAW, and started life as a screenplay that I will eventually write. It's set in Arizona and New Mexico in 1865, and I don't really want to tip a hand as to what it's actually about, but you'll probably pick up on it pretty quickly.

Hope you all enjoy it. If you do, you'll be seeing a lot more of my fiction excerpts in here going forward.

PAW

I: The Forge

The hills surrounding Parks Ranch were covered in tall grasses and weeds: feathergrass, Blue Grama and foxtails, thick and amber in hue now as the last of summer was trickling away and autumn threatened to take hold.

John Parks strode through the brush, lugging his pail and grateful he’d opted to wear his thickest pair of britches for his preparatory chores today. (Although he knew he’d have to spend the better part of an hour later picking foxtails and burrs out of the wool.)

The shack was nondescript, save for a stovepipe poking out of its tin roof. The small rectangle of rough-hewn gray oak planks sat atop a low hill that offered a perfect view of the Parks farmhouse where John lived with his father, Clifford. From just outside the shed, you could glimpse the entire perimeter of the ranch, as well as a half-mile of the only road leading into it, which was scarce more than two wagon wheel ruts, with a strip of scalped weeds between.

Reaching the door of the structure, John set down his pail with a thunk, then reached into his right pocket and withdrew a small metal key. He used it to pop the shackle on the bulky Smokehouse padlock that held the latch shut. He picked his pail up again with a grunt and stepped inside.

Fully half of the inside of the Parkses’ hilltop shed was taken up by a brick-and-mortar fire pit, with a crude iron bonnet overtop, venting up through the stovepipe in the roof and serving as the main failsafe in keeping the whole damn shack from going up in flames when the coals were burning their hottest.

John pushed his hat back on his head and, with another grunt, hefted the pail up onto a workbench that ran along the wall opposite the forge. He wiped a fine layer of sweat off his forehead with his arm, knowing the work was only going to get hotter from here. He looked down into the pail and took stock of the ore there, frowning as he did so. On any other boy of twelve, the expression would seem petulant, but John hadn’t felt like a boy for some years now. Those in his orbit tended not to think of him as a boy, either, and the dark circles under his eyes and the rigidity of his shoulders and his spine belied an adult in all but age.

He set to work, as there was much to do and the day could run away from him if he wasn’t careful. The first thing to do was to light the fire, and set it to burn red-hot and then white-hot by stoking the coals in the brick pit and working a leather bellows now and again in between his other tasks. Once the fire was lit and the bellows had helped breathe the first good burn into the coals, he plucked a hunk of ore from the pail. Using a ball-peen hammer, he busted the rocks up into pebbles, and then used mortar and pestle to grind the pebbles up into silt. Before he moved to a new piece of ore, he spent some time on the bellows again.

He tried his best not to think about how there were less than half as many hunks of ore this month compared to last. And that there was a time that he carried two full pails to the shed each month, and once upon a time he would have to take two or more trips up the hill, when there were four or five buckets full.

He filled three iron cups full of the ground ore, and placed them under the iron bonnet, onto a grate sitting atop the coals, which were now glowing nearly white. The air shimmered in the small space, despite him having propped the door open. Sweat cascaded down his face and down his back, and he had long since shed his shirt.

He took a break outside, feeling the heat billowing out of the shack in defiance of the light summer breeze that felt more refreshing than the coolest water he’d ever sipped. When he saw that the cups had begun to glow orange, he returned inside. Using rusted iron tongs, he withdrew each cup one at a time, careful not to spill a drop of the shimmering liquid metal inside. As he withdrew each cup, he carefully poured the fluid into a mold standing at the ready on the workbench. The resource finally exhausted, John set the cups on a brick ledge near the forge.

A short time later, he was lugging two pails of water up the hill to the shack. He doused the coals with the first bucket, instantly filling the structure with steam and smoke. Choking back coughs and blinking his watering eyes, John spread the coals using the pair of tongs, then doused them a second time. He fetched a disc of cast iron, like the lid of a pan, and covered the mouth of the brick and mortar furnace.

For a time, he sat outside on the bristly grass, checking his pocket watch now and then. When ten minutes had passed, he returned to the interior of the shed, which was slightly beginning to cool now. He pivoted the latches on the molds and took them apart, revealing the end product of his labor. In each mold sat twenty small cylinders, flat on one end and rounded on the other. Small metal sprues connected some of the bullets, and he popped those off and sanded down any rough remnants with an ancient file, seemingly composed more of rust than of metal.

Holding each one up close to his eye, he turned every projectile this way and that, knowing that no batch was perfect; he just hoped this set was free of any disqualifying imperfections. At last he was satisfied; just three of the bullets were off true, and it struck him that all three would still fire and would likely fly more or less true.

Into a square of chamois cloth he pressed his sixty silver pills, then folded the cloth and tucked it carefully into his back pocket. He shrugged back into his shirt and put the tools he’d used back into their place.

As he returned the padlock to the latch on the door, he saw that the sun had passed through noon and hung in the other half of the sky now. Gathering his pail, he started back down the hill to the farmhouse, his mind already focused on the next task: marrying casing, primer and power to each of his .36 caliber bullets.

Maybe, if there was time, he and his father might be able to have dinner together before moonrise.